In today's cities, the car and its various allies—freeways, asphalt roads, solid and dotted yellow and white lines, traffic signs, traffic lights, parking lots, parking signs, gas stations, charging stations, car dealerships, garages, and more—are so ubiquitous that they seem almost inevitable. This automotive arsenal, though imposing and intrusive, paradoxically blends into the background. Or rather, it has become the setting itself. Through repetition, the sight of these objects has become so commonplace that many people no longer notice or think about them.

Yet this normalization obscures the fact that urban planning was not always designed with the automobile in mind—far from it. In the space of barely a century, the car industry, in collusion with the ruling classes, has conquered cities and intercity roads. Multiple forms of transportation, such as tramways and passenger boats, were literally written off to make way for a road network designed exclusively for cars. The diversity of transport modes gave way to the monopoly of the automobile, rapidly and radically transforming both urban and rural landscapes. The following lines will attempt to expose this invasion, denaturalizing the car's presence in the process.

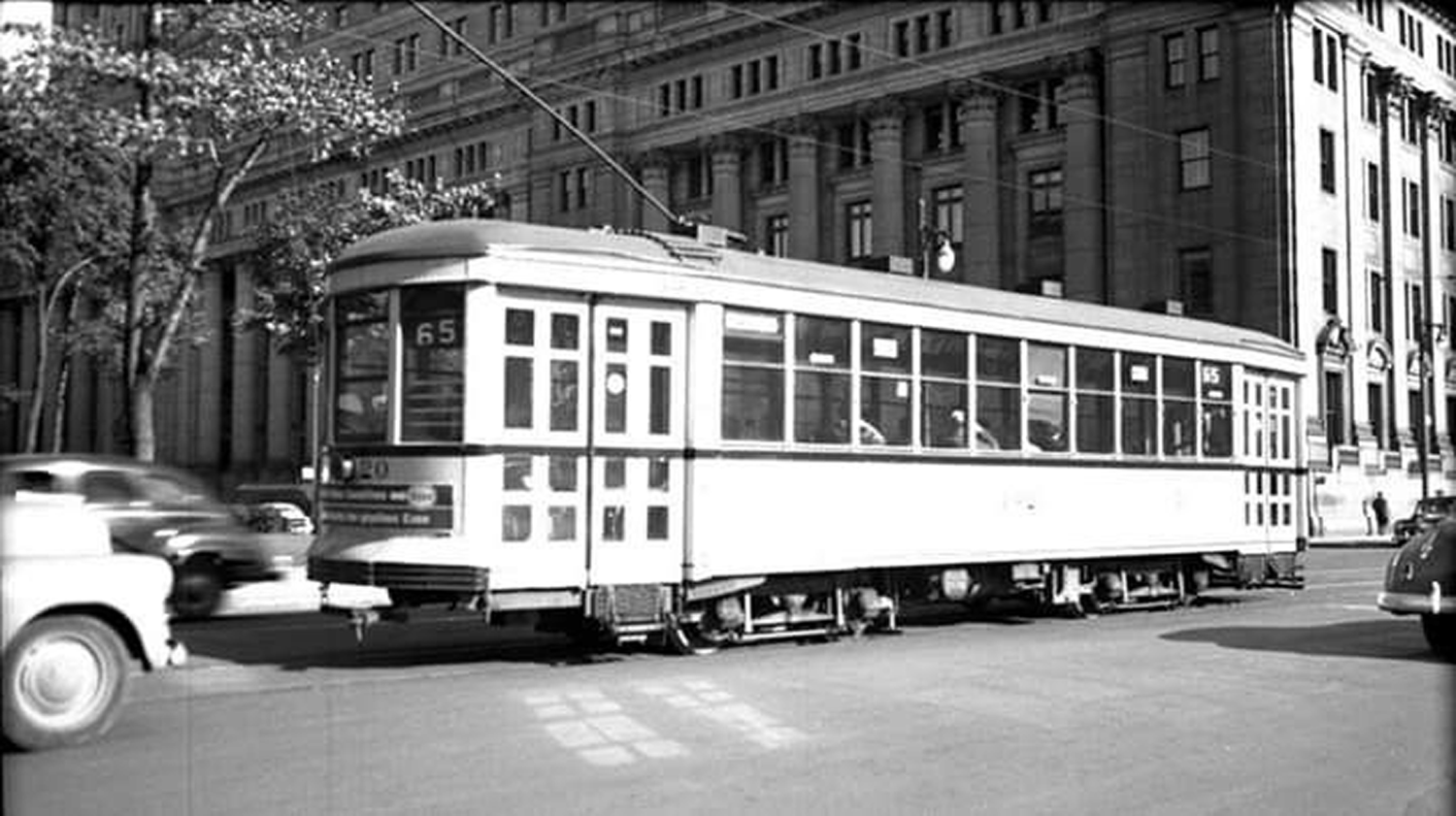

Before the arrival of cars, city dwellers moved about on foot, by bicycle, by horse-drawn carriage, or by tramway. The latter, invented in England in the first half of the 19th century, made its debut in North America mainly in the second half of the century. Urban transit in so-called Canada followed the evolution of that in the so-called United States, albeit with a time lag. In Montreal, the Montreal City Passenger Railway began operating long horse-drawn railcars on Sainte-Catherine, Dorchester, Wellington, and Notre-Dame streets in 1861. In Quebec City, the tramway appeared four years later, in 1865. Horse-drawn carriages continued to be used until the 1890s, when the first electric streetcars appeared. This period saw a meteoric rise in the number of tramway lines, operated by private companies.

At the beginning of the 20th century, with the emergence and democratization of the automobile, tramway companies became less and less profitable. An increasing number of motorists saw streetcars as a major obstacle to traffic flow. By the 1920s, major cities in North America and Europe faced a growing problem: traffic congestion. As profit-driven capitalist enterprises, streetcar companies gradually replaced their fleets with buses, which were much cheaper to produce. Unlike streetcars, buses did not require the costly maintenance of rails—a responsibility that had previously fallen on the companies. In contrast, asphalt roads were heavily subsidized by governments, which still invest billions of dollars annually into road infrastructure.

In 1951, the City of Montreal bought out the monopolistic Montreal Tramway Company to municipalize public transit. Within eight years, the forerunner of the STM replaced all of the city's streetcar routes with bus routes. Rails and power cables were removed, and in some cases, streets were simply paved over the old tracks without tearing them up first. By 1959, streetcars had been completely eliminated from Montreal’s streets.

Meanwhile, the automobile gradually took over, eliminating its main competitor—the streetcar. However, the space freed up by removing streetcars was not enough. At the time, neighborhoods were densely populated and streets were narrow. For the automobile to dominate, streets had to be widened, highways and parking lots created—no need to revisit the full list. In short, urban density had to be reduced to make room for cars.

Urban planners and political authorities commissioned what became known as urban renewal programs, a set of policies aimed at reorganizing and rebuilding urban environments. Between the 19th and 20th centuries, cities across every continent—from Buenos Aires to Sydney, passing through Marrakech—were radically transformed by this ideological and political movement. Streets were removed to widen those around them, and entire neighborhoods were partially or often completely razed to make way for highways, shopping malls, and parking lots, among other developments.

New housing was also constructed, but increasingly farther from city centers. This led to rising rents, directly linked to gentrification. The construction of the Jacques-Cartier and Champlain bridges, for example, extended the urban area to the South Shore, further adding to transportation costs for those displaced by these changes.

The destruction of these largely residential areas naturally required the expropriation of their inhabitants. The populations dispossessed and displaced from their living environments were predominantly working-class, racialized, and/or Indigenous. As a result, the main victims of these urban planning strategies—designed by and for the capitalist elite—were those already suffering from systems of oppression like cisheteropatriarchy, white supremacy, and colonialism.

It’s important to remember that the wave of urban renewal was historically initiated to "revitalize" rapidly built-up urban areas, polluted and degraded by the rampant industrialization of the 19th century. In elite jargon, "revitalization" is synonymous with gentrification—a euphemism that hides the intention to obscure poverty without actually addressing it. It is no coincidence that the neighborhoods targeted for massive destruction to make way for automotive infrastructure were inhabited by working-class people. In exchange, the overwhelming majority of these displaced populations were not rehoused, making it clear that the primary goal of urban renewal was to serve industries—automotive and others—rather than to address social inequalities.

For example, the construction of the Dufferin-Montmorency highway in Quebec City, inaugurated in 1976, "massacred a large part of the Saint-Roch district, dislodged people from their homes, and severely blighted the downtown area".1 The highway, which leads into downtown, is built high above the Saint-Roch district. Its ramps are suspended on massive concrete pillars, creating an unattractive, off-putting, and alienating space below. This project, funded with $70 million from the government, resulted in the destruction of over 500 homes in Saint-Roch; 450 people were evicted from the Saint-Jean-Baptiste district; 700 from the Limoilou district; and finally, 1,000 people from the Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix parish,2 which was completely erased by the highway’s construction—despite organized and sustained citizen opposition.

The conception of the city thus shifted from a place of habitation to one of work and commerce. Residential areas were relegated to the outskirts. Workers, now dependent on their cars, could commute from the suburbs to the city center for work and then return home in the evening. This population shift freed up space in the city to accommodate cars through urban renewal programs, which in turn spurred further suburban development. Working-class neighborhoods were dismantled under the pretext of overcrowding and unsanitary conditions, only to be replaced by bungalows on the outskirts—a development that made car dependency indispensable.

However, a nuance is necessary. Urban sprawl, capitalism, and colonial development are not unique to the automobile; these phenomena were already well entrenched in society before the automobile's appearance. Indeed, tramway and commuter train networks allowed workers to travel long distances between their homes and workplaces as far back as the 19th century (see the following article for more details). The construction of the railway network is closely linked to the colonization of the land and is often cited as an essential element in the birth of so-called Canada. The dominance of the automobile was also part of this process, continuing the colonial patterns of residential, industrial, and extractive expansion that were already underway.

Roads:

In common parlance, the term "road" is now synonymous with "motorway," despite the fact that its definition does not preclude its use for cycling or walking, for example. This semantic shift underscores the dominance of the automobile in the collective imagination of transportation.

Notes:

1 Ville contre automobiles. Ducharme, Olivier. Les éditions Écosociété, 2021, p.64