Montreal’s public transit, once touted as a hallmark of urban modernity, now stumbles under the weight of its own failings. Delays, inadequate service coverage, and high fares define the daily commute for thousands, while the elderly and disabled are left navigating an indifferent system that barely acknowledges their existence. These recurring issues are compounded by years of underfunding, a lack of responsiveness to the city's evolving needs, and a failure to serve the working-class communities most dependent on it. Instead, investments continue to favor car-centric infrastructure—wider highways, more parking spaces—while public transportation becomes a symbol of neglect. Transit-oriented development, which promises progress, too often ushers in rising rents, displacement, and speculative land grabs, leaving those who rely on the system most pushed out of their neighborhoods.

Montreal’s public transit, once touted as a hallmark of urban modernity, now stumbles under the weight of its own failings. Delays, inadequate service coverage, and high fares define the daily commute for thousands, while the elderly and disabled are left navigating an indifferent system that barely acknowledges their existence. These recurring issues are compounded by years of underfunding, a lack of responsiveness to the city's evolving needs, and a failure to serve the working-class communities most dependent on it. Instead, investments continue to favor car-centric infrastructure—wider highways, more parking spaces—while public transportation becomes a symbol of neglect. Transit-oriented development, which promises progress, too often ushers in rising rents, displacement, and speculative land grabs, leaving those who rely on the system most pushed out of their neighborhoods.

The city’s refusal to embrace fare-free transit, despite its success in other regions, reveals a deeper unwillingness to prioritize the public good. Instead, Montreal pours money into increased securitization, policing riders while cutting the workforce and services they depend on. Public-private partnerships, which now dominate infrastructure projects, serve profits rather than public needs, creating a vicious cycle of dependence on capital. These failures are not incidental but intrinsic to a system that privileges corporate interest and bureaucratic control over community-based solutions. True change will only come when power is returned to local hands, allowing transit to serve people, not profits.

Montreal’s public transit is a mirror of the broader inefficiencies inherent to the nation-state. Centralized decision-making, dictated from bureaucratic towers far removed from daily life, has left citizens alienated from the systems meant to serve them. The failures of transit are not isolated; they are symptomatic of a power structure that consolidates authority while cutting off local, context-specific responses. Public transportation, in theory, should be a democratic lifeline, but it remains under the state’s tight grip—detached, formulaic, and indifferent to the unique needs of working-class neighborhoods. This concentration of power reduces citizens to mere commuters in a system designed without their input, where decisions are made with little more than token consultation and gestures toward public engagement.

At its core, the state logic underlying public transit prioritizes control and efficiency over genuine service to the people. Plans are shaped more by the interests of the upper classes, reflecting a cold calculus of cost-cutting and privatization that alienates those who rely on affordable, accessible options. Market-driven policies and austerity measures strip public services of their utility, reinforcing a top-down approach that values logistical efficiency over human needs. Here, transportation becomes a problem of moving bodies—rather than ensuring accessibility, affordability, and equity. The state, in its pursuit of order and control, has forgotten the very communities it was supposed to serve.

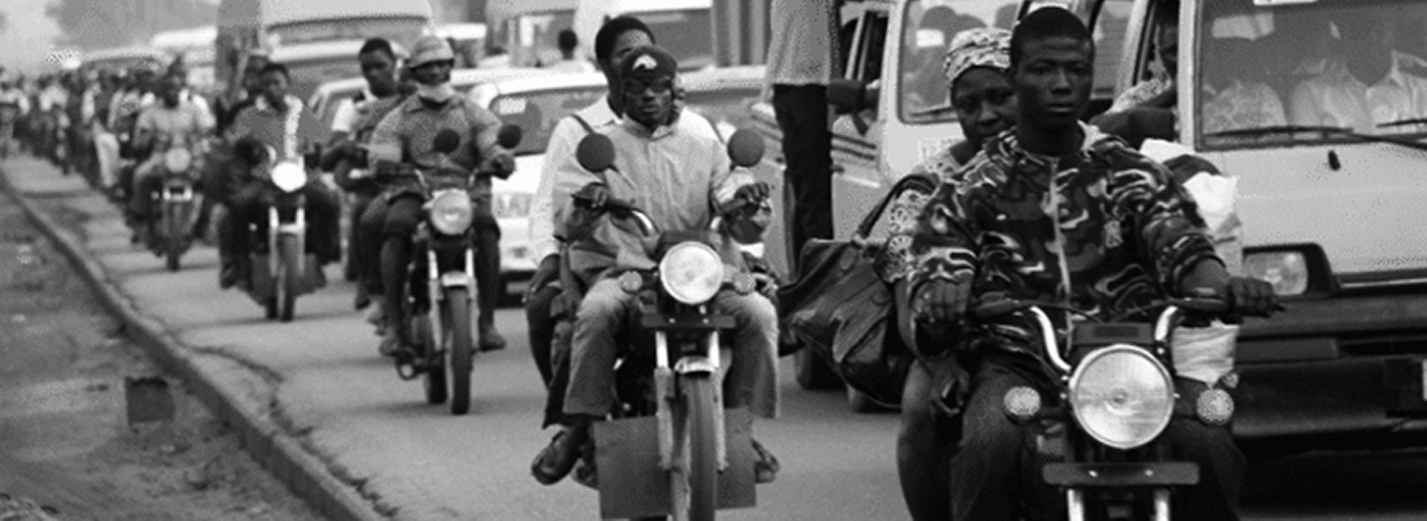

In the face of state neglect, communities around the world are crafting their own transit solutions, bypassing the maze of bureaucratic obstacles. In Mexico City, informal minibuses run by collectives—known as peseros—fill the gaps left by an underfunded and overstretched transit system. Similarly, in Nairobi, the Matatu system offers affordable and flexible transit, driven by community needs rather than top-down mandates. These grassroots networks are not only practical but are a testament to the power of local knowledge, adapting swiftly to the real, lived experiences of those who rely on them. Like the cooperative bike-sharing systems of Copenhagen or Bogotá, these informal alternatives embody the possibility of reclaiming transportation from the state’s rigid structures, offering decentralized, community-led solutions that better serve the people.

The plight of Brussels' navette drivers, who operate informal door-to-door shuttle services, highlight the unequal treatment of grassroots transit workers. These drivers are criminalized for providing essential transportation and accused of unfair competition. Their real offense, it seems, is not their service, but their informality—a low-tech, people-powered alternative that challenges the city’s preferred narrative of sleek, digitalized mobility solutions. While navette drivers endure precarious working conditions, corporate actors like Uber are celebrated for their “smart” innovations, despite employing similar, if not more exploitative, practices. The contrast is glaring: elite players are endorsed, while the very workers who embody true community-based transit are marginalized and pushed to the edges of legality.

In this world, corporate informality is rewarded, while subaltern mobility is criminalized, leaving innovation accessible only to those who can afford to commodify it.

The criminalization of informal transportation reveals a troubling disconnect between top-down planning and the realities of those who depend on these systems. Planners often dismiss these modes—whether okadas in Lagos, mototaxis in Bogotá, or jeepneys in Manila—as inefficient relics. In their rush to modernize, formalize and decarbonize, officials ignore the social fabric woven around these modes—mechanics, artisans, and vendors who all rely on the ecosystem they sustain. The cruel contradiction lies in the fact that, even as they criminalize these systems, authorities often fail to deliver on their promises of modernized alternatives, leaving communities stranded and livelihoods destroyed. Learning from those who live within and rely on these systems is not just a path toward mobility justice, but a foundation for true environmental justice—one that centers the people rather than disregards their solutions.

These alternatives, born out of necessity, embody practical local knowledge that thrives where state plans fail. Rejecting the contempt rooted in high-modernist planning, these systems push back against efforts to reduce transit to sterile equation of efficiency and control. Instead, these efforts respond to the nuanced, everyday needs of the people—filling in the gaps that state-run transit leaves behind. By democratizing transit, they reflect a deeper desire for local autonomy and direct control over essential services, offering a glimpse of what could be achieved if communities took power of their own transportation, free from the heavy hand of state interference.

Montreal, like many cities, is ripe for grassroots responses to its transit shortcomings. Drawing from global examples, residents could form worker cooperatives to challenge the state's monopoly on transportation. Imagine driver-run shuttle systems or neighborhood-based bike shares that cater to local needs, unencumbered by bureaucratic red tape. Such initiatives could flourish within community assemblies, where residents themselves decide how to allocate resources, allowing for more responsive and flexible solutions to the city’s transit woes. Transit would become a shared, communal resource, fostering deeper connections within neighborhoods while reducing reliance on top-down control.

The city's potential for decentralized, community-run transit networks echoes the broader critique of centralized state planning. A shift from the rigid, one-size-fits-all model imposed by the STM to locally governed mutual aid transit networks—ride-shares and neighborhood-run services—could transform the way citizens navigate their city. Rooted in direct democratic principles, these systems would be more agile and attuned to the immediate needs of underserved areas, bypassing the inefficiencies and alienation bred by the state’s high-modernist approach. In this vision, popular transit isn’t just a means of getting around—it’s an opportunity to reimagine urban life itself.

References and further reading

Bookchin, Murray. From urbanization to cities: Toward a new politics of citizenship. Cassell, 1995.

Planners Network. Disorientation Guide. 2nd ed., 2024.

Scott, James C. Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press, 2020.

William Boose and Benjamin de la Peña. “Popular Transportation: Where Planning for Environmental Justice Hits the Pavement.” Progressive City, November 2022.

Wojciech Kębłowski and Lela Rekhviashvili. “Moving in Informal Circles in the Global North: An Inquiry into the Navettes in Brussels.” Geoforum 136, November 2022.