Recently, several projects to convert commercial buildings into housing have been proposed in so-called Montreal. Examples include the proposal to demolish and convert Place Versailles into housing and Mon Dev's bourgeois housing project on the site of the former Da Giovanni restaurant in the LGBTQ+ Village. In both cases, these projects aim to revitalize underused sites and increase density near public transport lines, specifically the metro. While some might label these projects as environmentally friendly, they are not. On the contrary, they are detrimental to both the right to housing and the ecological struggle.

Indeed, in both cases, these are luxury projects intended for the wealthy, as they are privately developed. People living in the neighborhoods where these projects are located will be unable to afford to live there due to high rents designed to maximize profits for real estate investors. Additionally, these projects include a significant proportion of parking lots, which perpetuates a car-centric culture.

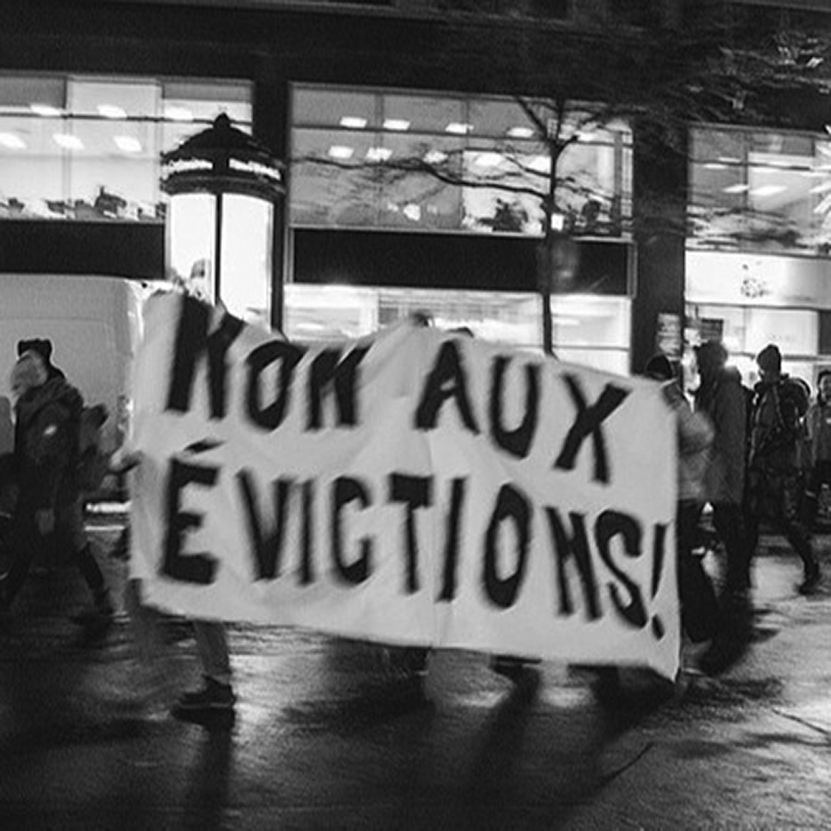

One might even question whether the developers genuinely intend for these units to be rented out or if they plan to list them on Airbnb and other short-term rental platforms, or simply leave them empty to write off as a tax loss. In the corporate world, capitalists receive tax deductions for company losses, making losses potentially profitable for them. At a time when homelessness and renovictions are on the rise, this type of real estate development is unacceptable.

However, there is an effective solution to tank culture, the climate crisis, and the housing crisis: the socialization of rental housing stock. In other words, it's the decommodification of housing—nothing more, nothing less. This strategy seeks to remove housing from the logic of the market and profit, ensuring it is managed by the people who live there, or by non-profit organizations, as in the case of housing cooperatives or HLMs (public housing managed by the Office municipal d’habitation de Montréal). This is not a plan for state ownership of dwellings, but rather a vision of self-management by and for the residents. As the ones most directly impacted by their living conditions, they would regain collective control over these units. Housing would no longer be constructed to enrich property managers but to serve the well-being of its residents.

One example of this model is the city of Vienna in Austria. In Vienna, over 60% of the population lives in social housing, which is twenty times more than in so-called Montreal. Residents can keep their homes for life and even pass them on to their descendants, eliminating the risk of eviction. The city builds over 5,000 housing units each year, ensuring there is no housing shortage, even though residents can stay if their income rises. The maximum income for accessing these units is twice the average income, allowing the majority of the population to qualify and retain their housing if their income increases. Rent represents 20% to 25% of income, compared to 50% (conservative estimate) to 80% in the private sector in so-called Montreal.

Viennese social buildings even offer amenities typically reserved for luxury buildings in Montreal. These include rooftop swimming pools, meeting rooms, day-care centers, shops, restaurants, and even communal gardens for residents.

Since 2019, real estate developments over 5,000 square meters in Vienna must allocate two-thirds of the units to social housing. The city collaborates with the Department of Spatial Planning and utilizes a development fund to acquire land. Single-family homes are banned—this type of zoning doesn't even exist—eliminating the "not in my backyard" phenomenon.

Vienna also recognizes the inseparable link between transportation and housing. For example, before developing a major public housing project, the city built a subway line to serve the new area, aiming to reduce car use to just 20% of trips. By socializing, it becomes easier to design efficient neighborhoods around transit stations, planning housing and transportation simultaneously. In short, the city develops for the benefit of the population and the planet, rather than for wealthy capitalists.

For all these reasons, even capitalists are forced to acknowledge Vienna's success. In 2023, The Economist—certainly not a far-left media outlet—ranked Vienna as the top city in the world to live in. The city earned a 100% score for stability, healthcare, education, and infrastructure, which includes housing and public transport.

As Vienna’s example shows, it is possible to do things differently. In so-called Montreal, we could socialize 100% of the rental housing stock and abolish private property ownership altogether. Private ownership has proven to be a failure, as evidenced by the worsening housing crisis. The goal of private developers is to maximize profits and send them overseas to avoid paying taxes. These capitalists are indifferent to people's well-being, even if it means some are left to sleep on park benches due to their greed. As long as their offshore accounts continue to grow, that’s all that matters to these real estate sharks. It’s time to collectivize housing for the benefit of both people and the planet.

Sources

Oltermann, Philip. “The social housing secret: how Vienna became the world’s most livable city.” The Guardian 01/10/2024, s.p. Online. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2024/jan/10/the-social-housing-...

La Presse en Autriche | Logement social : les leçons de Vienne | La Presse. Online. https://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/2021-10-13/la-presse-en-autriche/loge...

Vienna’s Unique Social Housing Program | HUD USER. Online. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr_edge_featd_article_011314.html